The Future of the Peace Corps – and How to Stop It

First Published on Medium

Tl;dr—Long-ish thoughts on the current and future states of Peace Corps the organization as someone who is leaving it after 5 years at its DC Headquarters.

I want to sketch out some thoughts on the current and (possible) future states of the U.S. Peace Corps and its direction as an organization.

But first, bear with me as it requires a little bit of set-up and context for some features unique to the organization and experience of volunteers around the world.

While this article will probably be of interest to Peace Corps employees and past and present volunteers, it also dips into themes that could be relevant to those interested in the politics of international development, volunteerism, bureaucracy, and technology to some extent.

Your mileage may vary.

My window into the organization

For the first time in ten years, I have no official connection to the Peace Corps, and I have felt an itch to reflect on this journey and some observations that have stuck with me.

I must first say—that this process of moving on has been a little surreal. The nature of my relationship to the institution has changed over the years, through the various roles I’ve been lucky to have—volunteer, campus recruiter, and most recently as a staff member in Washington, D.C., where I voluntarily stepped down after 5 years of service just last month.

For me, it’s not simply a position that I’m leaving—it stacks up to nearly ⅓ of my life.

When discussing my ‘time in Peace Corps’, it invokes everything from the experience of haggling for prices in a local village market in Mananjary to wrestling with spreadsheets and outdated SharePoint from my cubicle in the D.C. home office—quite dissimilar activities, yet both in the service of the same organization. It’s just weird to think that the same organization that taught me how to ensure Section 508 Compliance also taught me how to poop in a bucket.

And I’ve loved my time there (not so much the bucket). In the whole of my tenure, I have had incredible and countless opportunities to travel the world, to develop lifelong friendships, to be forced out of my comfort zone, and to be both challenged regularly and given incredible room to learn and grow as a human being.

I’ve seen broader challenges of the organization as well—ones that are both general and specific to Peace Corps, for example—like how to think about and assess risk in an ever-changing world, how to talk about thorny issues like sexual assault and harassment in a workplace that includes 66 countries, and how to balance freedom of expression while remaining anchored in the spirit of diplomacy and foreign service.

I firmly believe that the Peace Corps continues to be one of the great beacons of American idealism around the world, as cheesy as overwrought as that sentiment is in 2017. And it’s a tangible, individual-to-individual force for good that is one of the best bangs-for-our-congressionally-appropriated-buck around when it comes to crafting better people who live on this planet.

But I’ve also come believe that even institutions like the Peace Corps are more fragile than we imagine (and more than we would hope). They require us, as engaged citizens, to be ever-vigilant when it comes to ensuring that their efforts are constantly steered towards their missions, that their activities respond to the real-world challenges and opportunities of the people they aim to address, and that their stewards (staff and volunteers) are equipped with the resources and earned trust to carry out their work.

In short, the Peace Corps can continue to be that beacon of idealism, of problem-solving, and of good works—but there’s nothing that makes this happen automatically.

It’s going to continue to take a pooling of combined efforts in order to ensure that Peace Corps is on the right path—and it will require effort from past volunteers, current volunteers, future volunteers, the staff of Peace Corps Washington D.C. (including its leadership, both appointed and career and around the world), as well as for the general public too—to hold some feet to the fire and make sure we get there in creating the world we wish to see for ourselves.

So—all that said, here are three areas that ˆ think Peace Corps ought to focus on in order to (re-)orient itself towards being the most effective and living up to its potential as much as possible.

…A disclaimer

It’s important to state up front that my views and opinions are obviously shaped by my own experiences. Peace Corps is one of those blind-men-elephant examples of a thing where everyone brings their respective experiences to the table and while none are necessarily wrong, none can obviously be wholly true and complete, either. So, while I always do my best to question my own assumptions and privilege in a space, I would be the first to admit that my experiences do not and cannot speak for all.

I should also add here that even if (when) I have harsh words for the Peace Corps, it’s not because I have an axe to grind, or I’m trying to get unresolved agitations off my chest. Peace Corps, like any institution, is not above reproach—and criticism of the organization or even some of its members should not be registered as an attack on the institution. I’m a true believer in this institution’s ideals, and I recognize that too that seldom is the hard work ever done.

1. Remember the past.

The Peace Corps has one of the most interesting and important histories of any government agency in the last generation. Understanding that history is critical in situating any perspective that looks towards what Peace Corps ought to look like and how it ought to be oriented for generations to come.

The creation story

If Peace Corps didn’t already exist today, it’s hard to imagine that it would be (re-)created in today’s world of 2017 and with the current political, social, cultural, and economic environment. Just think about it—the idea that you could spend federal tax dollars on sending (mostly) recent college graduates with little experience to far-flung villages and cities for two years at a time to serve local interests…

Well it would seem fairly…peculiar.

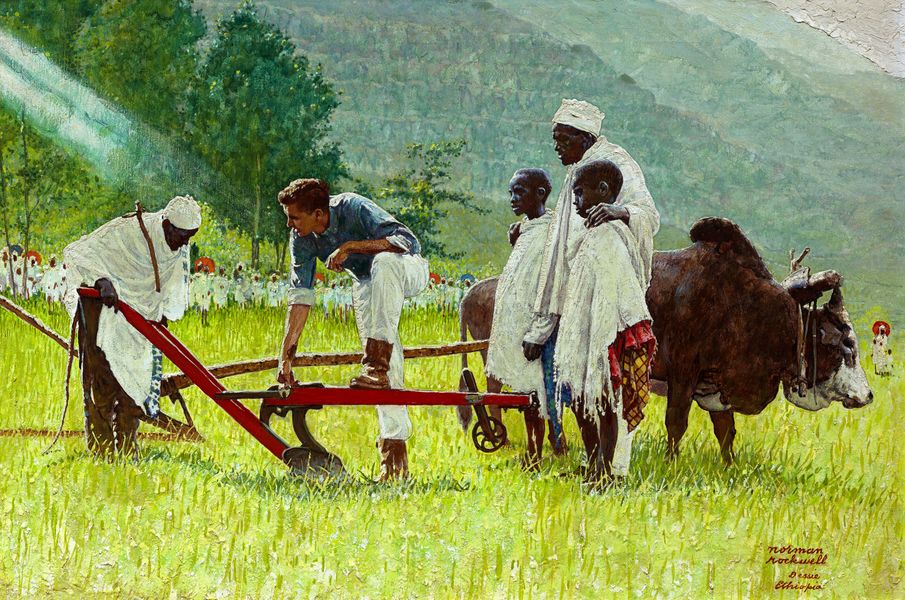

Thankfully, we don’t have to create Peace Corps today—it’s already been done for us—founded in the forges of the early 1960s in whirlwind era—newly-elected Kennedy administration, rising progressive and social equality movements, and a global theater seeing the sunset of colonial authorities, Woodstock—there was a lot going on, to hear my parents describe it.

Peace Corps was both a response and perhaps in some ways a catalyst of the era, that helped converge ideas and energy around youth activism, global engagement, and democratic participation. It was a perfect storm of circumstances to create an institution at the federal level whose mission is literally “world peace corps and friendship” and has a literal dove in its logo.

And it wasn’t as if Peace Corps’ inception was any ho-hum event, either. The story itself is a fantastic narrative that is a little surprising hasn’t been put to film yet (seriously—read about it, it’s insane). It’s got:

- A 2 A.M. speech by candidate Kennedy on the steps of the Michigan student union…student activists hand-delivering a petition to Kennedy on a tarmac in Ohio promising, “…if you’re serious about it, so are we.” * The president’s own brother-in-law tapped to run the agency before it even has congressional approval. * A young Bill Moyers who, when up for senate confirmation hearing to be the youngest deputy director of an agency (ever) at 28 years old, quipped, “I’m actually 28 and a half.” * Staff sleeping under desks at all hours, recruitment events held in strip clubs (by accident…we’re told). * A postcard from a nice volunteer in Nigeria that almost sunk the entire endeavor.

And that’s not even getting into the sit-in at Peace Corps when armed returned volunteers took over the building in 1970 as a response to American involvement in Cambodia.

Peace Corps has an amazing history—and it’s important to understand the upheaval that occurred in its inception in order to appreciate what it took to carve out the Peace Corps as the unique creature of the federal government that it is.

It’s this history that comes into play when ideas are tossed around that Peace Corps ought to be merged with other service organizations (been there), expanded (it used to be twice as big), or have a digital sector (officially in 1999, but working in telecommunications from the get-go).

And it doesn’t stop at the water’s edge of being a federal agency — it’s an institution with a unique history in every single country and community that hosts the Peace Corps—each with their own stories worth telling and re-telling.

My favorite recent story is that of of Peace Corps in Liberia when volunteers were evacuated during the Ebola crisis, and Peace Corps staff and vehicles were used by the CDC in their efforts. It was a tragic circumstance that provided an otherwise hard-to-see illumination of the deep roots of Peace Corps’ accumulated trust over the course of 50 years of hundreds of volunteers engaging at the local level—as CDC staff found it remarkably more efficient to travel with ease and be trusted when associated with the Peace Corps brand and the local Peace Corps staff.

If we are serious about not always reinventing the wheel, then actually looking at the wheels we’ve invented over time wouldn’t be a bad place to start.

Institutional memory

Peace Corps service for volunteers is 2 years—technically 27 months if you include the 10 weeks of training in-country while you are still considered ‘in-training.’

The 2-year time period is interesting—when you’re young and weighing career options, it seems like an eternity, and when you’re (even slightly) older and looking at career with some degree of perspective, two years seems like a flash. Nevertheless, as a Peace Corps volunteer, as with any job, you get into a rhythm of short, medium, and long-term projects and investments—some of which will hopefully outlast your own tenure and can be handed off to the next bright-eyed group of trainees as they take your baton.

This continuity of attention is particularly important in communities where volunteers serve, as the cycles of social and economic development are most helpfully addressed and measured not in summers and semesters but in decades and generations.

To complicate matters, volunteer entries and exits are staggered throughout the year according to training class and sectors of work. In many cases, it’s logistically challenging or impossible to have volunteers do the sort of important hand-off coordination to incoming volunteers that would both ease their transition and set them up to hit the ground running. Remember too that rookies are only 10 weeks into learning the local language, while the seasoned volunteer has been haggling at the market for 2 years—it’s a sort of ‘Peace Corps Law’: to your neighbors you’ll never be as fluent as your predecessor; and your replacement will never be as fluent as you.

A final challenge for Volunteers (of about 1,000 more that I’m not talking about) — it’s possible to extend your service, even more than one year at a time (and then to sign up to serve again in a completely different country, which believe it or not happens with some regularity.)

Now—in all of this talk of volunteers, you would be forgiven if you were to think that that’s all there was to it. That the volunteers show up to their village, rucksack and solar charger in hand, ready to change some hearts and minds about these Americans. But obviously it takes a tremendous behind-the-scenes effort from local staff, Americas serving in the country offices, and from the folks serving in the home office of D.C., rounding out the effort with recruiting offices in the U.S. and campus recruiters sprinkled around the country.

Peace Corps staff have similar challenges to those of volunteers—in that they deal with staggered inputs, expectations on hitting the ground running, foreign cultural environments that take some getting used to (by this I mean cubicle culture in D.C.). Add on to that the complication of election cycles that determine agency leadership (the top two positions are chosen by the White House and senate confirmed, while 30-ish more leadership positions are filled by the White House’s choosing, who then pursue their particular initiatives and projects which themselves spawn requisite re-organizations and potential hiring/sunsetting off of career staff positions.

There is an additional unique feature of Peace Corps staff employment known as the ‘Five-Year Rule’ (just the U.S. full-time staff actually—the local staff that are hired in the countries where Peace Corps volunteers serve are exempt.) It’s essentially a timer that starts on your first day that counts down five years until the last of your contract (appointees get this too, so they have two countdowns to worry about).

This ‘rule’ was put in place near the retiring of the first generation of Peace Corps staff like Shriver, who wanted to ensure a spirit of continual renewal, of fresh ideas and staff within the organization, and to avoid bureaucratic stagnation. If you’ve ever worked in an office with a Cheryl from Accounting who has been there for 30 years and won’t budge on a new process, then you know what he was getting at. You don’t want to get into a position where that experience becomes stagnant and rather than, as one colleague put it, “be convinced you’ve get 10 years of experience when you’re really got just 1 year repeated 10 times.”

Much ink has been spilled on both sides of the ‘is the 5-year rule worth it’ or not—and to be perfectly honest, I go back and forth on this with some regularity. There are a lot of moving targets of projects and priorities for an organization that has such a large and diffuse footprint already. You want to bring people in who have the right set of experiences and insights to solve challenges, particularly when they’ve solved those same challenges in other environments. You also want them to be hungry and motivated to commit to projects and seem through.

But you also don’t want them to only have two good years in them before they start looking elsewhere, or to invest in someone so heavily for years only to have all of that tacit knowledge walk out of the building on a random Tuesday.

Regardless, it’s no surprise that this creates obvious challenges around the institution being able to properly manage and prioritize long-term projects, particularly when combined with White House election cycles and high turnover of volunteers carrying out the mission of the agency in the first place.

These days, I’m of the school of thought that as we are seeing the sunset of careers tied to a single organization, that the 5-year rule will go from being something to avoid (extensions, becoming a private contractor, or getting special exemptions from the Director) with pride and beam about to colleagues—“I’ve been here 15 years—ask me how I’ve done it!”— to something folks simply use a service deadline— “I committed to 5 years of service here, and I chose not to leave until I saw my projects through…”.

But I might be particularly biased on this one in particular.

2. Forget the past.

Now that I have you keyed in to the agency’s storied history and the importance of institutional memory in general—we’re now going to throw it all out the window.

The Peace Corps icon

Because the agency of the Peace Corps has such an interesting creation story, it should come as no surprise that it’s developed a sort of mythical, almost unassailable status as a cultural icon over the years.

What I mean is that Peace Corps-the-institution has a lot of cultural weight attached to it—mostly from what I would argue is a positive and honor-worthy attachment. For example, telling someone that you served as a volunteer or that you have family members or close friends associated with the Peace Corps—it carries with it a sense of pride and connectedness—a phenomenon similar to an association with sports or schools or hometowns.

This is of course aided by a steady influx of new volunteers who perpetuate the status of Peace Corps-as-icon, keeping the cycle alive.

At the same time, such a strong association with the ‘myth’ of Peace Corps legacy and reputation can be challenging when faced with criticism or efforts to reform. Criticism—from inside or outside the organization—can be seen as attacking the institution itself (and its members, who may take personal issue with critiques or even with the speaker’s standing to make such a criticism).

I’ve seen many honest efforts at dialogue cut down or dismissed outright as indulgent or invokative of the “no legit Peace Corps volunteer would critique…” in the vein of the No True Scotsman argumentative fallacy.

I’m painting a fairly stark picture in the abstract — but I probably do not have to dig too deep to show examples where Peace Corps has responded slowly and/or unsatisfyingly to criticism, and where to reform have stalled or failed to gain traction.

These circumstances are not unique to the Peace Corps, of course. Any bureaucracy is going to face challenges that force them to prioritize accusations of misdeed alongside calls for reform alongside constructive criticism alongside…well, good old-fashioned trolling.

The particular challenge that Peace Corps faces with respect to its own mythological status is that over time, the reflex to defend the institution is easier than it is to be open to legitimate dissenting voices—and in the case of Peace Corps, often those voices want nothing more than to improve the organization in the first place. When left unchecked, it’s possible that this hubristic posture can play a role in creating environments that lead to very tragic consequences for Peace Corps volunteers.

By not allowing itself to be open having its history and legitimacy questioned in ways big and small, the Peace Corps risks calcification of its ability to pivot and adapt to changing climates—it becomes a cottage industry for its own storytelling that looks back on itself and can’t believe how amazing it really is.

It makes it harder to trust that the road you’re going down is the one you ought to be on—things like data quality, impact, comparative performance—they are all made that much more taboo as a topic of general critique.

If the ways of doing things are continued simply because it’s how it’s been done in the past (and things were perfect in the past), then you have already narrowed your scope of possibilities for the future.

From a more bureaucratic lens, you’ll end up in a monkey-experiment dilemma where everyone is doing all they can to carry out the status quo, worried that any change will bring down the whole system altogether—though they know not which change if any could do it, so they touch nothing.

An example of this that has driven me crazy for years is simply the reporting of the official number of Americans who have served in the Peace Corps—often reported now as ‘more than 225,000’, when the internal numbers suggest something closer to 200,000. It’s a paltry point in the scheme of things, and no one would argue that Peace Corps is a paragon of data quality in the world, but come on! It also serves double duty as just a great example of needless puffery within the organization. To correct the figure would force someone to admit that it was wrong in the first place (and then re-verified about 1,000 times)—and that would be absurd, right?

Generation gaps

Many of the individuals with leadership positions at Peace Corps served as volunteers themselves earlier in their careers, which really does go a long way towards bridging the understanding that staff will have of the volunteer experience, and all of the rich nuances associated with it. It is a cliché (yet true) that every volunteer experience is different. And yet, it can be an incredible relief to know that the folks crafting policy in Washington D.C. are not so removed from the often isolated, awkward, rewarding, and challenging experience of serving as a volunteer in the field.

At the same time, staff both in Washington D.C. and particularly in overseas post have the cards stacked against them when it comes to empathy with modern volunteers.

One, there is a significant age and sometimes generational gap between the staff members and the volunteer on a general level (the median age of the volunteer is just 24 years old). I’m not sure that the Volunteers are spending all of their living allowance on avocado toast, but I’m sure you’ll find some angry staff member writing a memo about it somewhere.

Two, staff are asked to be both guide and policy enforcer to the volunteer, which puts them in the awkward position of being responsive and supportive *to volunteer needs on the one hand, and *enforcing policies to protect the volunteers on the other hand. And the methods and styles available to them can often feel…quite paternalistic (restrictions on travel areas and times, great attention to alcohol over-consumption, notices for volunteers not to leave their village too often, etc.). Tack on to that that staff are all the while meeting the bureaucratic burden of a needy Washington home office that requires constant and time-consuming reporting data, surveys to be filled out, and ridiculous demands that stretch credibility with the home office’s understanding that the staff are literally in other countries with different time zones with actual work to do.

And three, most of the current staff experiences occurred prior to the ubiquity of global connectivity, computers, mobile phones, smartphones, data plans, social media, and video conferencing.

Think about that—as I want to stay on it for a moment.

In other words, many staff experienced the Peace Corps when it was still this romanticized version of the ‘isolated volunteer’ — the lone adventure of a young idealist anthropologist/writer as they set foot in foreign lands and become completely immersed in the local community, the nuances of the local language, the local environment, and the service of their volunteer job every minute of every day—checking in with family only through postcards and letters sent sparingly every few weeks and which would then take months to hear the associated response.

Whatever reality there was to the isolated volunteer *experience, it has largely disappeared and been replaced by the experience of the connected volunteer.*

The connected volunteer is perfectly adept at juggling multiple smartphones, is able to check-in with friends on a regular basis, posts Facebook status updates, tweets about village life, instagrams the realtime success/failure of their project, reflects on their daily life with blog updates, and video conferences with their family in the U.S. as easily (or more) as eating dinner with their neighbors next door.

Now—we could divert right here and go down a rabbit hole discussion around the experience of the modern Peace Corps volunteer and compare it to the experiences of volunteers in other eras and in various countries and communities—just on the connectivity face alone. It’s fascinating and anyone who says they have it figured out one way or another is flat out lying.

Regardless of whether or not the volunteer experience is significantly different, this empathy gap between current volunteers and staff extends to headquarters and the senior leadership as well. At the end of the day at HQ, I found that anyone who’s job had to do with volunteers and technology spent more of their time convincing senior leadership that digital things by themselves would not break the volunteer experience (smartphones, GIS, knowledge-sharing platforms, and mobile chat apps, to name just a few), than they did in the service of scaling tried and tested technologies that volunteers were already successfully leveraging. It was a lot of work, and often enough, it wasn’t worth the effort to convince leadership that they weren’t going to destroy the agency or put it at incalculable legal liability in the process.

Peace Corps needs to learn how to forget in order to recapture the spirit of its forging in the first place. It needs a Schumpeterian ‘creative destruction’ from time-to-time to rebuild its approach from the ground up, from the Volunteers first and outwards to the mission of the agency. In today’s world, that means using smartphones and digital repositories, online courses with badging certification and instant feedback, crowd-sourced project management and scaling across not just location but across time as well with well-documented case studies and examples of achievement and innovation over the years for others to pick up the baton.

If you want to have your mind simply BLOWN with an incredibly prescient article from the in-house Volunteer Magazine in 1967 written by Stuart Awbrey and Paul Reed where they anticipate the changing of the guard from the ‘old’ volunteers of the early 1960s who were raised on books and newspapers to the ‘new’ volunteers of the late 1960s raised on television and radio (using Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media as the framework).

It’s one of the spookiest reads I’ve had in a while where you can replace “television” with “Internet” and it could be published today. Also it had this incredible nugget:

But further up the piece, there is a great paragraph about the challenges of looking to the future through the lens of our past. I find it also not a little ironic that I found this while searching to understand how the Peace Corps approach to technology had changed over the years.

3. Stop the future.

What to stop

My worry for the Peace Corps is not that it is suddenly appropriated out of existence, or even something more mundane like be merged with another agency like USAID or the State Department (and thus perhaps marginalizing its overall influence and scope.)

Rather, my worry is that the anchor that is Peace Corps’ history and unique place in the American story will actually serve to weigh down and in fact limit the organization—and by extension the volunteers’—ability to innovate, adapt, and to learn forward into this next generation.

My worry is that Peace Corps’ approach on a range of issues will be shown to be dated and ineffective, eventually to the point where the most capable, talented, and motivated potential volunteers will instead look elsewhere to make their positive impact on the world. By limiting the supply of *those *individuals, Peace Corps ranks will skew towards just…mediocre…performers and limited impact. It will tip towards an unvirtuous cycle of increasing ineptitude and irrelevance.

It’s the kind of thing that simple analytics around number of applicants annually won’t tell you, and might in fact mask a decline already in-place.

My worry is that Peace Corps prioritizes Trump Administration acquiescence by acting career staff who preemptively cut staff positions prior even to congressional budget approvals, and scrub mentions of climate change work preemptively—out of a combination of risk aversion and appeasement by folks with ‘acting’ imposter syndrome.

My worry is that the kinds of things that are going to hurt Peace Corps the most are actually going to be the incremental, complicated, and unworthy news stories that are not able to break through the competing and dominant news cycles of Puerto Rico, North Korea, and American football.

My worry is that anecdotes like the gaff by Christiane Amanpour might be more and more commonplace—

In 2008 Christiane Amanpour illustrated America’s declining role in the world > by telling a foreign policy conference, “There was a Peace Corps.”

After the session, a former volunteer named Jon Keeton angrily corrected CNN’s > chief foreign correspondent: “There still is a Peace Corps.”

As author Stanley Meisler recalls, Amanpour blushed but pointed out that there > must be something wrong if someone like herself did not realize the Peace Corps still existed.

My worry is that Peace Corps’ collective ability to converge that spirit of American idealism, youthful optimism, and committed engagement around the world, will simply recede over time, washing away into the seas of the previous generation’s history.

The reason is simple and important enough to harp on again—the success of Peace Corps depends on the volunteers—whose efforts are supported by the Peace Corps organization and staff—in the volunteer’s efforts to immerse themselves in the culture, to integrate with their communities, and to work alongside their host colleagues.

A Peace Corps of tomorrow would build from the primacy of volunteers as a first > principle.

From the primacy of building a volunteer-first organization, we recognize that volunteers are themselves flexible, adaptable, oriented towards change while wise in incorporating the lessons and mythology of the past. They are the laboratories of experimentation. And they are the experienced and adept group of individuals, who by their nature and talents, have the freedom to try things in new ways, to learn what works and what doesn’t in different environments, to scale solutions, and to communicate success stories and failures alike.

In my time with Peace Corps, I am utterly convinced that there remains so much untapped potential within the spirit that drives people to Peace Corps in the first place.

And quickly on that thread, I am not even convinced that an overseas extended service is the be-all-end-all of what volunteerism for peace and service is all about. I have written before about how technologies like virtual reality and digital mapping can bring a different immersive experience to someone, and there is much yet to be explored on this front.

Besides, there is a strong argument to be made that that it is the Peace Corps that is the foundation for a future Starfleet. I’m just saying. We have a lot of work to do, but that’s the kind of organization it ought to be shooting for.

Again, I might be biased.

Peace Corps would also do well to learn from its colleagues, and dare I say competitors in this space. I’ll grant that in the early days of Peace Corps, it was the only show in town. Now, that’s not only not the case, but the oft-repeated internal mantra that Peace Corps is somehow the ‘gold standard’ of service volunteerism can only be heard while eyes are rolling. Organizations like VSO in Britain and Canada, JICA in Japan, Teach for America, Code for America, and many more are doing really interesting things with all kinds of different models of recruitment, of centralized versus decentralized organization, of retaining alumni for recruitment, of external partnerships, of funding—the list goes on.

And Peace Corps needs to do a better job of supporting volunteers and coaching staff on how to fit technology and digital tools into their work, and show them ways in which the technology can serve as an enabler rather than as a distraction. Staff need to embrace that viewing projects and programs from a technology lens is not something that’s ‘optional’ nor is it a moonshot project out of an ‘office of innovation’.

Integrating technology is a fundamental way for volunteers and their host communities to have a greater and more effective impact. There shouldn’t be internal hand-wringing and internal debates about the merits of that approach. Even Mark Zuckerberg called for a digital peace corps earlier this year.

Peace Corps needs to send a clear message that rather than shying away from innovation, creativity, and novel solutions, that it embraces them and sees them as a critical component not only to their local work in their community, but as important for the entire Peace Corps community writ large, and thus for all the countries where volunteers serve and will serve.

The reality is that Peace Corps doesn’t necessarily need an office that focuses on innovation (as it had but was unfortunately and unceremoniously shut down—a story and a rant for another day).

But it certainly needs to promote the idea of innovative practices and modern problem-solving to its existing challenges. I’m not even talking about full-scale Design Thinking seminars for staff. Even simple and straightforward things like using social media effectively, leveraging video as a communication tool, and recognizing that people aren’t reading the 300-page manuals programming offices across government and the international NGO sector are churning out.

There are a lot of places to get started—but only if you widen your scope of possibilities to include them.

Getting Started

Peace Corps’ mission is more relevant today than ever before.

Peace Corps is needed in order to foster the sort of face-to-face connectedness around the world that seems harder to come by in a world dominated by digital economies of insulated bubbles, Facebook friends, and Twitter followers.

Peace Corps also acts as an open invitation to serve—an inspirational focal point that allows idealism and practicality to converge on a single point of service.

I believe we can use Peace Corps’ unique history and its tethering to the ideals of an optimistic and tumultuous 1960s to slingshot ourselves from the 2010s into the next generation of service, fellowship, and global connectivity.

If we are being honest, then we recognize that significant changes are going to require difficult but important shifts in how the organization operates, how it prioritizes its mission, and how it inspires the next generation of potential volunteers to spend their time in service overseas.

If we are going to do this, it’s going require a remembering of what’s worth keeping while letting go of what’s only a part of history. We will need to Marie Kondo-ize the Peace Corps—and hold in our hands that which brings us joy, and let go the things that are better left to the good will of history.

It’s going to require us to build the future of Peace Corp together—as volunteers, as ex and future staff, as Americans, and as global citizens.

And we don’t have to wait. In the words of Arthur Ashe:

Start where you are, use what you have, do what you can.

At any given moment this year there are a little over 6,000 Peace Corps Volunteers serving in around 65 countries around the world. The annual Peace Corps budget of around $400M. In the grand scheme of things, it’s not a lot—but it ought to be more than enough to get started.

Ten years ago (almost to the day), I was sworn-in by U.S. Ambassador to Madagascar Niels Marquardt (pictured below), who himself had been a Peace Corps volunteer in Rwanda in the 1960s. He said during his remarks to a group of idealistic volunteers about to set out to our home for two years on a mission of peace and friendship:

…what you’re doing represents the finest of the human spirit…to embrace > selflessness and actively seek to help those whom you’ve never met is an objective of the highest order of what we can achieve.

It’s a good place to start.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in the history of Peace Corps, I can’t highly recommend When the World Calls by Stanley Meisler. It is a history of the Peace Corps from the beginning up to Obama — fantastic stories and contextualizes the entire history of the organization and the institution.

For interesting propositions to change/reform the Peace Corps, I would recommend checking out these links from which I’m indebted for thinking through in my own musings:

Sargent Shriver calls for a new Peace Corps | Peace Corps Online

Shriver’s own recommendations for Peace Corps changes back in 2001.

Peace Corps Comprehensive Agency Assessment, 2010

This is probably one of the best and unfortunately continually relevant documents as to the state of Peace Corps and its challenges.

Peace Corps Transition Team Gives Obama a Roadmap for the Future | Peace Corps Online

Much of this is still incredibly relevant and sits on the table from the previous administration.

Ludlam/Hirschoff Plan to Save the Peace Corps | Peace Corps Worldwide

Manifesto of sorts from a Volunteer couple who served in the 60s and again the 2000s. Really great read.

The New Peace Corps |Yale Journal

Great article from one of Peace Corps’ more forward-leaning staff alumni (and served as country director) that I was forwarded only after an earlier draft of this piece went out—it’s similar to this except shorter and more well-written. So—go here first. : )

Tech can reshape the U.S. Peace Corps and bridge political divides | TechCrunch

Former RPCV and former Obama Science advisor weighs in on Peace Corps leveraging the digital age.

Grow Up | The American Interest

Essay from a former Country Director on how Peace Corps ought to shift its focus.

And of course a hat-tip to Jonathan Zittrain’s incredible book The Future of the Internet for providing the idea of a little hook on the title of this essay.

My own future

While I was sad to leave Peace Corps, I had a lot of time to prepare myself as I was adamant about sticking to the five-year once I had made the commitment (both to stay and not to over-stay). It’s been a wild ride.

But I also couldn’t be more excited for this next chapter, as I’ve started a position as a User Experience Designer for a firm in Washington, D.C., I’m in the midst of launching Propr Things, a startup 3D-printing company, I just released version 2.0 of the ICT4DGuide.io, and I’m looking into getting a cat.