Peace Corps Volunteers Should Embrace Digital

There is growing buzz around putting technology in the hands of Volunteers and development workers. Peace Corps Volunteers, for example, are starting to arrive in countries with smartphones, laptops, tablets, and e-readers where even five years ago the Volunteers in the field were hesitant to pack away such “luxuries” (or liabilities).

The explanation for the shift is not simply one of the progress of technology, nor even simply demographics of current Volunteers that are part of the “digital generation” or of their being millennials that are ‘addicted’ to their phones and computers. The reasons are for more interesting, compelling, and potentially disruptive.

Why Volunteers are bringing devices

There are essentially four reasons why development workers in general and Peace Corps Volunteers in particular should consider their use of technology in the field than they have in the past.

- The technology context where Volunteers serve is almost unrecognizable today from even a decade ago.

- Volunteers are are indeed entering their service much more comfortable with the available technologies - many of them have least rudimentary knowledge of computer systems, while more and more come with programming and software development skills that they are anxious to use.

- Seemingly everyone - from the White House to Non-Governmental Organizations to local counterparts are excited and invested in the prospects of technology to address existing problems and situations.

- Finally, a convergence of the previous three points leads to an environment of Volunteers, counterparts, and communities where the existence and use of technology for both personal and professional purposes is less taboo or even something remarkable.

The tech boom in the developing world

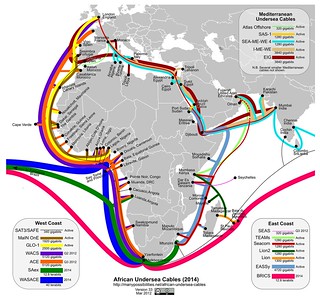

The technological and telecommunications landscape of the areas where Volunteers serve has changed rapidly over the last decade. This map of Africa for example (where the greatest percentage of Peace Corps Volunteers serve), shows the evolution of undersea cables that connect Africa to the world Internet at high speeds.

It’s not just about undersea cables either. As the mobile market has expanded, manufacturers are producing low-cost handsets at very affordable marginal rates—an unsaturated market of potential phone buyers and contract signers are seen as an untapped market by both manufacturers and telecom companies, and demand for voice communication, texting, and Internet services is incredibly high.

Low-cost feature phones (dumb phones) can be purchased in any market in major cities, and most smaller towns and even villages. Even smart phones are beginning to arrive from Chinese manufacturers employing the pre-built Android operating system. The fact that these devices are being bought, used, tweaked, traded, and integrated into daily life makes it easy for Volunteers to do the same.

Volunteers are digital natives

The average age of the Volunteer is 28 years old, while the median age hovers around 25. Incoming Volunteers come from a generation of young adults who have been interacting with and applying digital technologies for nearly their entire lives. Given that many of them have college educations, they are comfortable using digital tools for research, writing, communicating with the peers and colleagues, reading news, current events, and educational materials, and generally in contexts where technology literacy is part of their job and livelihoods.

Certainly the average Volunteer is not a computer programmer, and cannot be expected to be a sort of computer whiz or be able to magically build websites and software to meet the challenges of the day - but it can certainly and safely be assumed that on average, the Volunteers are comfortable with low-level technology use expectations, and will often see more efficient uses of technology as an aspect to their projects in Peace Corps (think grant-writing, coordinating conferences, writing lesson plans and calculating grades, etc.)

Technology is a government and development priority

The White House has led a charge (Note: link broken as of February 2017) for greater data openness, transparency, open-sourcing, crowdsourcing, and itself sponsoring dozens of initiatives in this space. The international development community too has seen great potential in backing greater transparency, communication, and data-driven decision making. There are innovation labs, maker spaces, creative hubs, and hacker communities popping up both domestically and internationally creating some really interesting driving forces for technological change and updates.

Government agencies have been tasked, for example, to find new and innovative ways to communicate not only with the general public, but also to communicate with the scores of software developers, designers, and tech-geeks that are able to find new and interesting ways of solving old problems. Helping Peace Corps Volunteers to more effectively and efficiently engage the three core goals of Peace Corps by exploring new tools and techniques is certainly in line with this thinking.

Digital devices fit into the context and culture of Peace Corps work

Volunteers are very good at arriving into a situation - be it a community, a classroom, or a conversation - and assessing what they know, what they would like to know, and how to go about getting to know more. They ought to be, as it’s one of the core concepts of the 10 weeks of training that Volunteers are taught when they arrive in their host country. As teachers, for example, they learn about the level of their students, the lessons that resonate or fall flat (and why), the teaching aides that have an impact, and their relationships to colleagues.

By night, when the lessons are over, they can pore over manuals of exercises and lesson plans, finding examples that they can adopt, adapt, and modify to make their own for use the next day. They quickly learn how to ignore outdated materials, time-wasting resource scavenger hunts, and ill-fitting texts and lessons.

It’s not hard to see the advantages of carrying around a mobile device that weighs less than 10 ounces, can hold hundreds of thousands of pages of text, and be flexible enough to allow new information and material to be downloaded. But Volunteers are also savvy enough to be aware of the fact that if they don’t have electricity, then it might make more sense to make use of a device that lasts weeks on its battery rather than hours.

If they don’t want to stand out in their community, they might prefer using a feature phone (dumb phone) day-to-day rather than re-iterate their special status in the community by always toting the latest iPhone.

Finally - a Volunteer might recognize the important social implications of carrying tried and true books and paper documents to a school staff meeting - items to be readily shared and discussed, as opposed to a novel tablet device that is both foreign and intimidating.

Putting devices into the hands of Volunteers

It would seem that the question of “if” has been answered, and now we need only ask the question of “how” — how do we best construct a sustainable method for providing Volunteers access to critical devices and tools?

Volunteer needs and opportunities

Peace Corps Volunteers are adept at quickly assessing their needs and preferences where they work - and the posts that support them are good at this as well. Posts are able to recognize the short and long-term needs of their Volunteers, and to respond to the particular project requirements and professional development.

Where Mongolia is the one Peace Corps country where certain Volunteers can receive training and the use of horses for transportation, there will be certain countries where Volunteers use Kindles, Android-powered phones, or feature phones (dumb phones).

Device overview

First things first - e-readers and tablets are not interchangeable. While there is an overlap in functionality and form, the typical devices differ enough in features, costs, and constraints to make it important enough to draw a line in the sand for most conversations.

Typically, tablets are referring to the world of Apple’s iPads, Microsoft’s Surface RTs (and perhaps Surface Pro), and large Android devices. Tablets are typically touchscreen, with bright, power hungry displays and exist in an ecosystem of apps and programs.

They may not completely replace laptops and desktop computers, but they can come quite close for many uses. E-readers on the other hand are typically the Amazon Kindles (though not the Kindle Fire - that’s a tablet), the Barnes and Nobles Nooks, and Sony Readers.

These are specialized devices - offering few apps if any, are typically defined by their e-ink screens that are made explicitly for reading, typically have a much greater battery life, and are smaller so they can be comfortably held in the hand and be lightweight.

E-readers (like Kindle Paperwhite, Keyboard, etc. [but not the Fire or Fire HD]) offer a pretty amazing reading experience – they last for weeks on a charge, are easy on the eyes, and can be read in sunlight. But they force you to read very linearly – if you’ve ever tried flipping back and forth between pages or documents rapidly, you realize how inefficient this can be. Great for novels, awful for manuals, dictionaries, reference materials.

Smartphones limit one greatly by the screen size. Statistics on this show a huge difference opinion on how practical this is–some loath reading any sized text, others can breeze through War and Peace without breaking a sweat.

But for reading, scanning, flipping around documents, this is usually much faster and made easier with features of the platform (both iOS and Android have great advantages in momentum gestures – swiping quickly and seeing your progress in a document, pinching to zoom in and out of detailed graphs, texts, and figures, etc.)

**I’m just going to reiterate here that this is a personal blog—I’m not involved in procurement for the federal government, and none of this is meant to speak for official agency positions on organizations, companies, devices, etc.

Formats and functions

The most critical feature after the use of the document – what formats are we talking about. Spreadsheets are the least friendly off of a laptop or desktop – but even then I’ll use something like the CloudOn app (iOS) for quick panning and zooming.

If you have Google Doc spreadsheets, then the native iOS and Android apps are actually a fairly efficient way to move around in a spreadsheet–but still annoying, I find. PDFs are a nightmare in Kindles. I know that many folks will read the box, upload PDFs to an e-reader and call it good – but talk to anyone that’s tried to read 5 PDFs on a Kindle and you’ll get blank stares – it’s just nearly impossible because of the resolution and screen size.

Oh – and don’t rely on Amazon’s service to convert PDFs to MOBI or e-readable formats – a lot of it becomes garbled. Sometimes this works ok, most times it doesn’t. ‘DOC’ formats are a little better on Kindles, but unless it’s really well organized, it’s still going to be slightly annoying to read it on a Kindle.

Finally – EPUBS and MOBI files (easily interchangeable with an application like Calibre [cross-platform, open source]) that have been designed for e-readers are great….if done well.

In the field for development aid workers

Sorting out all of the various uses, the different formats, the wide selection of devices and technologies to choose from can be fairly daunting. We then add a layer of complexity when we start to think about where these devices are going to be used, who is the intended audience, and how to maximize their value in the hands of the Volunteers.

There are certainly plenty of things to be excited about when thinking of the marked advantages that such a device could bring to the Volunteer experience. They allow the Volunteer to carry around literally hundreds of thousands of books, and the devices are quite portable.

They can assist in learning foreign languages with built-in dictionaries and lookup functions. They allow someone to jot notes, or highlight text. They are extendable so that new and free books are available instantly to download or sync to the device.

They allow the reader to be discrete about the type of material they are reading - a bigger deal than you might think in some developing country contexts.

In the classroom for students

These advantages are so obvious that there are many projects out there looking at how e-readers can supplement or even replace books in the classroom in developing country contexts.

The most notable of these is Ghana with the Worldreader program. Worldreader just released a report last year on a years-long study with e-readers for students and teachers.

Without diving too much into it - I think the one really interesting piece came out around ownership, accessibility, and the potential for device breakage (higher than one might think).

A wonderful framework of e-reader devices in developing country classrooms by Mike Trucano at the World Bank.

Tying it back to a realistic use-case

I reflect back to my own days as a Volunteer and remember my most-commonly used materials: lesson plans, bits and pieces of official Peace Corps manuals, official policies, and handouts within manuals.

I would have MUCH preferred a smartphone with an SD card – I could easily transfer items, didn’t have to worry about size limits, didn’t have to worry about connecting to USB or WIFI with my Kindle, could read while traveling, could quickly flip through and pan around documents, etc.

I would have brought a Kindle, too, but probably only to slog through The History of Madagascar and/or War and Peace, which is what many of the current Volunteers are doing.

Future-proofing

After reading this post, one might be tempted to think that the digital scene for Volunteers, their projects, the various locations they service in, and their own preferences and contexts are simply too varied and confusing to take any action at all. It’s all so mixed up that any global directive and policy is going to be a wasted effort.

I would argue that while the tools coming online today are reason to be excited, and that we don’t actually have to venture into the shark-filled water of specific devices, locations, and uses.

Rather, we should divert our focus to the content and materials themselves.

This might seem obvious at first, but when the majority of our documents are delivered in either Word documents or PDF published-proofs, it’s hard as an end-user to make use of that on a web-browser, e-reader, or Smartphone.

It will involved a bit of a transition on the production end to also think about how best to develop for HTML, for text-based materials, for EPUB files and for documents that won’t be printed in DC’s government printing office but rather on a low-toner inkjet printer at the Internet cafe in-country.

We can do this — we need only the will and the right perspective to act.